UNDERSTANDING THE NOTION OF COLLECTIVE IN TAGORE’S ENVIRONMENTAL PRACTICES

- abhilashaspot5

- Aug 20, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Aug 26, 2025

Introduction

The India we see today is paralyzed with dead rivers, grey skies, declining ground water-tables, waning forests accompanied by escalating volumes of untreated wastes which further takes the form of a literal garbage mountain. Meanwhile, through destructive and carelessly conceived projects, the tribal and peasant communities are incessantly pushed off their lands. This is the contemporary Indian scenario that lacks a sustainable thought and in the name of development, our precious environment is at stake.

Our purported ‘civilized’ society has alienated itself from Nature. Ramachandra Guha mentioned a report in his book ‘Environmentalism: a global history’ (2012), which states that Nature can never be managed well unless the people closest to it are involved in its management … Common natural resources were earlier regulated through diverse, Decentralized, community control systems. But the state’s policy of converting Common property resources into government property resources has put them under the control of Centralized bureaucracies, who in turn had put them at the service of the most powerful. Today, with no participation of common people in the management of natural resources, even the poor have become so Marginalised and alienated from their environment that they are ready to discount their future and sell away the remaining natural resources for a pittance. (Guha, 2014, p. 156)

About a decade ago, there existed a prodigious man, ahead of his time, on this very subcontinent. Shri Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) was a polymath, an extraordinary personality and a boon for India. Nature was his companion right from his childhood. He has written numerous poems, short stories, songs and plays which talk about Nature and the precious environment. The relevance of his thoughts on the environment can be very much connected to the current conditions. This article discusses the concept of ‘Community-Engaged Practices’ in the domain of Art, its association with Tagore’s practices which he initiated in the early 20th century in Bengal and the importance of community engagement in the current environmental circumstances.

The notion of Community Engagement

“Every human being is an artist, a freedom being, called to participate in transforming and reshaping the conditions, thinking and structures that shape and inform our lives.”

― Joseph Beuys

All forms of art that are created, communicated or experienced by others, is social. Art based on social interaction has been identified as “community”, “collaborative”, “participatory”, “relational aesthetics”, “dialogic” and “public” art among the many titles. Social practice is an art medium focusing on engagement through human interaction and social discourse. (Helguera, 2011). Socially engaged art aims to create social and/or political change through collaboration with individuals, communities, and institutions in the creation of participatory art. Claire Bishop very well explains:

“What emerges here is a problematic blurring of art and creativity: two overlapping terms that not only have different demographic connotations but also distinct discourses concerning their complexity, instrumentalization, and accessibility. Through the discourse of creativity, the elitist activity of art is democratised, although today this leads to business rather than to Beuys. The dehierarchising rhetoric of artists whose projects seek to facilitate creativity ends up sounding identical to government cultural policy geared towards the twin mantras of social inclusion and creative cities. Yet artistic practice has an element of critical negation and an ability to sustain contradiction that cannot be reconciled with the quantifiable imperatives of positivist economics. Artists and works of art can operate in a space of antagonism or negation vis- à- vis society, a tension that the ideological discourse of creativity reduces to a unified context and instrumentalises for more efficacious profiteering”. (Bishop,2012, p. 16)

The element of ‘participation’ is key in socially engaged art practice and the artworks created hold equal or less significance than the ‘collaborative act’ of creating them. In his book ‘What We Made: Conversations on Art and Social Cooperation’ (2013), Tom Finkelpearl outlines social practice as “art that’s socially engaged, where the social interaction is at some level the art.” The practice of socially engaging the public/ communities can be allied to activism as it often deals with current societal-cultural-political issues and/or environmental issues. The artists/ practitioners working in this field spend much of their time integrating with the communities which they wish to collaborate, help, educate or simply share a dialogue with.

“Socially engaged art functions by attaching itself to subjects and problems that normally belong to other Disciplines, moving them temporarily into a space of ambiguity. It is this temporary snatching away of Subjects into the realm of art-making that brings new insights to a particular problem or condition and in turn make it visible to other Disciplines” (Helguera, 2011, p.5)

Socially engaged practices allow in recognizing ecological interdisciplinary art practices that aim to create environmental awareness, sustainability, preservation of biodiversity and much more. Eco-artists/ practitioners’ work nurtures collaboration and engagement between humans and the land and for achieving this, various tools and techniques are incorporated and are highly process-based and research-oriented. It is a multidisciplinary field of action. Artists/ eco- practitioners work in collaboration with the public and undertake complex projects to accomplish in the contemporary social and environmental scenario.

Tagore’s vision of Ecological Harmony

Both philosophically and in reality, Rabindranath found a deep connection between man and nature. His experiments in regenerating the dilapidated social and economic life of Bengal’s villages from the early 20th century was a pioneering effort. His conceptualization and methods adapted for its solution stand out for more than one reason.

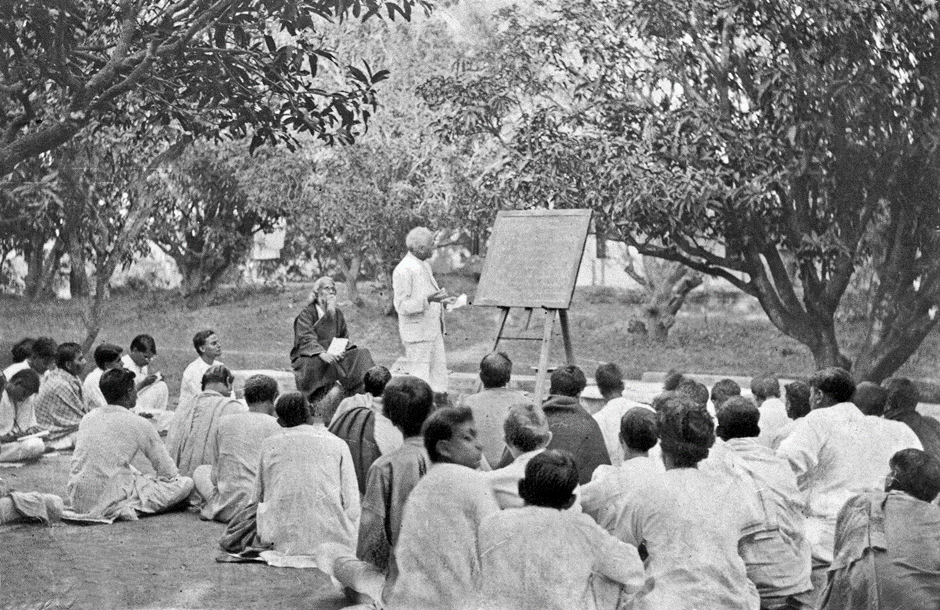

The poet’s concept of Indian topovan is evident in his experiments in the field of education at Santiniketan, West Bengal, where he spent most of his life. This can be seen in the arrangement of boarding schools cum ashram of pupils and thus reflects his concerns with man’s proximity to nature. He anticipated the transformation of the dry landscape around Santiniketan along with rural reconstruction. Under the guidance of British agriculturist L.K. Elmhirst, Sriniketan was developed in the 1920s, which is close to Santiniketan. Tagore’s social attempts in harmonizing nature and mankind through various ways are reflected through these actions and deeds. (Banerjee, 2018)

He was well aware of the destruction of the environment by fast urbanization, industrialization, deforestation, and other related evils and condemned the same. Whether rich or poor, air/water/soil pollution affects everybody but the poor is the most affected. He churned out poems, plays and short stories emphasizing the need to protect nature.

“There are invisible writings on the blank pages of these desolate places which tell the story of how some civilizations had for ages elaborately busied itself in preparing its own burial ground.” - Rabindranath Tagore, City and Village (Chaudhury, 2012)

He anticipated an introduction of a collective practice that would catch the popular imagination and make people plant trees together irrespective of class, creed, gender or religion; a practice that celebrates the love for nature. Consequently, he introduced a community festival known as ‘Vriksharopana’ (planting of trees) in the year 1928 in Santiniketan. He cherished this ceremony and said:

“Trees of the earth are cut for several necessities and the earth became naked by plundering its shadows of clothes. It increased the temperature of the air and damage the fertility of the soil. The homeless forests tend to warmth by an unbearable hit of the sun. Keeping these words in minds, we held the ceremony of tree planting which is nothing but the function of filling in the gaps of plundered mother’s wealth.” (The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore, 2007)

He got this feeling already about a hundred years ago that it was important to plant more and more trees in order to save this planet. Undoubtedly he said “The danger is imminent because of deforestation. To save the danger, we have to recall the god of the forests, so that it can save this land and can bear fruits, and allows shadows.” (Bhowmik, 2012)

This utsav or festival is celebrated in Visva-Bharati on 22nd of Shravan (the fifth month in the Hindu calendar), the death anniversary day of Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore. It is celebrated each year artistically and with a simplistic approach. People participating in the festival, both local folks and of Visva-Bharati, recite his songs while going for the plantation of the sapling. It’s a picturesque scenario every year in Santiniketan. Music, dance, and Vedic chanting further invokes Nature’s fertility and symbolizes the ever-recurring youth of Santiniketan. This ceremony of planting the trees can be regarded as a representation of the reverence towards trees, towards the protection of trees and forests and therefore, protection of the biodiversity and the maintenance of the ecological harmony.

He also announced another very important ceremony which is celebrated in most of the South-East Asian countries, i.e., Halakarshana or the Ploughing Ceremony. Right after the ceremony of Vriksharopana held at Santiniketan, this ceremony is practiced at Shriniketan, as a symbolic tribute to the act of ploughing the land. It aims to endow the work of ploughing as nearly a sacred act, a dignified one. Every year, an important dignitary of the country is invited to drive the plough on the 23rd day of Shravan. During the festival, Rabindranath said:

“Greed was increased when people took the gift of the earth, after conquering farming from the forest; finally, the monopoly of the agriculture sector was to remove the forest. Cutting the trees for different needs and taking away the shades of the earth, they started giving it naked. He made the winds heated, and the soil became fertile. The forest of forest-shelter today is so damn sad. Keeping this in mind, the program that we had done a few days ago is the tree-plantation, the welfare of filling up the motherland with looted children.” (The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore, 2007)

This tilling of land was started by Tagore as a tribute to the pastoral livelihood in the year 1929 and since then, Visva-Bharati is celebrating this festival with an aim to promote healthy cultivation practice with righteousness and dignity.

The notion of deep ecology reveres both human and non-human entities of the ecosystem with an egalitarian attitude. This is evidently exemplified in the nature-centered/earth-centered approach of Rabindranath’s actions couple with his writings. The poet’s philosophy of Unitarianism clearly reflects his universalism in the facets of human-nature relationships. (Banerjee, 2018). Rabindranath’s asserted on the moral principles and the eternal values that once regulated in our Indian society and culture. This formed the foundational base of universality and humanity and the inherent integrative form of social relationship. He highlighted the fact that man establishes himself in his world as a creator through efforts to reshape and reform the material and the social world in order to make it through a higher order of existence. This cannot be said as just a linearity of change; it is the fullness of existence that man always strives for. It is the process that he tried to realize and recreate on this earth. The poet stated that the relationship is the fundamental truth of this world of appearance.’ Through the interrelationship between various aspects, whether social or with nature, the inner characteristic pattern of relationship gets established. When the parts are separated, the inner manifestation of the totality is dissipated. His concept of humanity lies at the core of his idea of society and underpins his concept of totality, unity and the ideals of the morality of goodness (mangal or kalyan). His perception of totality was more analogous to the gestalt theory. The collective practices were conceived as more than an organized system. (Sinha, 2019)

Conclusion

The damage caused by the brutal consumerism to our ecology and environment is a matter of concern as the evils related to it have now added impetus in the capitalist society. In the name of development, there have been unobstructed misuse and abuse of natural resources which has further led to the destruction of the world’s ecological balance and biodiversity. The alteration and seizure of traditional practices by new methods and techniques have created a new list of environmental problems. The contemporary world is facing a serious ecological crisis and thus triggering great damage to human-nature sensibility. Present-day human being has lost the connection and harmonious relationship with nature. Rabindranath Tagore throughout his life fought against this economic exploitation of natural resources and promoted a healthy relationship with our environment. Rabindranath encouraged modernizing and rebuilding the society by inculcating rational attitude through education, changes in interpersonal relationship and behaviour, collective and egalitarian ideology. (Sinha, 2019). He can be regarded as the greatest environmentalist of this age who preached the virtues of reverence, humility, responsibility and care towards Mother Nature.

Collaborative and community work have the power to uplift the cause of protecting the environment and balancing the biodiversity in India. The attachment of social theory with Art might sound new and novel but it had its roots in this subcontinent a long time ago. Pablo Helguera says that “Social practice avoids evocations of both the modern role of the artist (as an illuminated visionary) and the postmodern version of the artist (as a self-conscious critical being).” (Helguera, 2011). Eco-practitioners’ actions are environmentally impactful and advantageous, they recognize humankind's’ moral duties to respond to the human-caused ecological crises of the present-day by enacting environmental reform. Their work nurtures collaboration between humans and the land, which fosters a sense of ownership and responsibility within people to restore their own landscapes. Their practices and methods prove to be great examples of social and ecological rejuvenation in the public domain. In the public sphere, these kinds of projects can engender momentum through engagement and education along with the present-day media and technology. The creative and innovative means through which the participants in a community/socially engaged practice workout are the driving force to achieve the balance between man and nature.

To cope up with the current ecological disorder, it is necessary to merge different fields of study to find a solution to anthropogenic problems like climate change and biodiversity loss. Ecologically concerned art practices can play a significant role by encouraging dialogue and offering visions of desirable sustainable futures, both informed by and informing an “environmental value system,” or “ecological ethic,” as well as the concept of ecological justice. (Wallen, 2012). Experts from diverse fields should join hands and must penetrate their knowledge to a large number of the public which resides in rural areas. The poisons of patriarchy, superstitions, capitalism, industrialization ought to be overthrown to achieve a progressive society where the Women and Mother Nature get respect and reverence.

*****

References:

1. Guha, R. (2014). Environmentalism: A Global History. Penguin Books.

2. Joseph Beuys Quotes. Retrieved from the Goodreads website https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/8310.Joseph_Beuys

3. Helguera, P. (2011). Education for Socially Engaged Art. Jorge Pinto Books.

4. Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. Verso.

5. Finkelpearl, T. (2013). What We Made: Conversations on Art and Social Cooperation. Duke University Press Books.

6. Banerjee, A. (2018). An Ecocritical Perspective: Tagore’s Gitanjali and Selected Verses. In Ecocriticism and Environment. Primus Books.

7. Choudhury, P (2012). Tagore, the Father of Environmentalism, Sagnik Books.

8. The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore. (2007). Atlantic Publishers & Distributors (P) Ltd.

9. Bhowmik, D. (2012). Rabindranath Tagore: An Environmentalist and An Activist. In International Research Journal of Humanities and Environmental Issues. 1(5), 10-12

10. Sinha, D. (2019). A Poet’s Experiment in Rebuilding Samaj and Nation: Sriniketan’s Rural Construction Work, 1922-1960. Birutjatio Sahitya Sammiloni.

11. Wallen, R. (2012). Ecological Art: A Call for Visionary Intervention in A Time of Crisis. Leonardo. 45(3). 234-242

Comments